“I wouldn't go in if I were you,” Russ said. "Something bad happened in there."

I raised an eyebrow toward

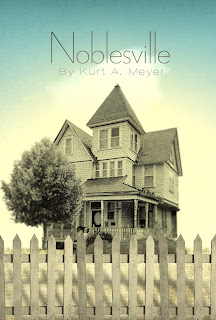

the 1870s Italianate farmhouse, pushed askew by a backhow, looking like a house

from a Dr. Suess story. “No house

has ever given me a more threatening vibe,” he mumbled, shaking his head.

We were at an old Hamilton

County farmstead. Russ asked me to help him move cut stone steps he planned to

use at his historic home in town. We were restoring houses a half block apart.

The neglected farmstead was about to be leveled for a new subdivision.

I’d arrived late and wanted

to check out the house for architectural salvage, but if Russ said don’t go in,

I wasn’t going in. He’s a no bullshit guy. We loaded the cut stone (and amazingly

found a native American ax head under the slabs) and left.

I started doing salvage when

I was restoring my first home. Living on a teacher’s salary and restoring an

1890s Victorian cottage while raising children made buying reproduction hardware,

rebuilt vintage light fixtures, and fresh-milled woodwork unthinkable. Salvage

was the only answer.

Empty, aged, abandoned

houses – once they’re free of the clamor and glare of a modern homeowner’s

technology and decorating and the echoing vibe of personal belongings, their

own rich, deeply burnished personality can radiate like a rolling wave spun from

a 150 years of babies made and babies born, weddings, parties, dinners, blizzards

and thunder storms, Christmases, son’s off to war, funerals, engagements and breakups, Sunday brunches and lonely

afternoons, tens of thousands of cooked meals and just as many canned goods grown

in the yard and stored in the cellar, faithful dogs and sleepy cats, grandma’s

last breath and babies’ first steps, creating an emotional rush that can greet you with welcoming warmth, but occasionally a cold shoulder of rebuke.

|

Assorted escutcheons salvaged over the course of 25 years

|

I started out picking trash.

Pushing a child in a stroller on evening walks I’d find a pile of star bricks

discarded behind a garage, knock on the back door and be told I could take

them. I built my first patio with street paving bricks taken from an alley

where my town’s judicial center is now and built the table that sat on that

patio with disguarded oak planks found in an alley while walking a child in the

evening.

I began digging in dumpsters parked

in front of old house renovation projects. The dumpsters almost always yielded

a decorative floor grate or long plank of quartersawn oak baseboard. These were

hauled home, filling my little garage and back basement.

It allowed me to replace my

1960s front door with a proper ornate, stained glass door with a matching

transom overhead, both salvaged and outfitted with salvaged hardware cast

with elegant floral patterns. My porch had been enclosed with cinder block and

cheap aluminum windows. Riding my bike to the dentist’s one day, I parked in

his garage and saw a complete set of porch posts and ornate brackets stored in the rafters. Once I tore out the cinder blocks and shabby windows, those porch

posts and brackets were put in place.

And most of it had been free. Most people I encountered thought it was trash and thought me odd for wanting it.

It may have been a fascination with archeology that kept me salvaging even when I didn’t need anything. My garage got filled with goose neck toilets, porch posts, fireplace mantels, and hand made Civil War-era doors, all of which I had absolutely no use for, they’d simply been in the collapsing old house or dumpster for the taking. I couldn’t bear to see them go to a landfill. Eventually I held a garage sale, promoting it weeks in advance to historic preservation groups throughout the central part of the state.

It may have been a fascination with archeology that kept me salvaging even when I didn’t need anything. My garage got filled with goose neck toilets, porch posts, fireplace mantels, and hand made Civil War-era doors, all of which I had absolutely no use for, they’d simply been in the collapsing old house or dumpster for the taking. I couldn’t bear to see them go to a landfill. Eventually I held a garage sale, promoting it weeks in advance to historic preservation groups throughout the central part of the state.

|

| Carved stone pulled from an Indianapolis demolition site. |

I bought the rights to

salvage a couple houses and ducked into buildings to unscrew and pry thing off,

just days, and at times, moments before they were demolished. Once, in

Bluffton, Indiana, salvaging woodwork on the 2nd story of an 1880s

house that was being slowly demolished by a crew with sledgehammers and a Bobcat, I

finished my work to find the stairs had just been pulled free. I had no way

to get out. Fortunately, my father-in-law knew I was there and checked in to

see how I was doing, shouting up from the street. He brought over a ladder, I

tossed all the woodwork from a window into the yard and climbed down.

By the next day the house

was gone.

|

| Nickel plated hinge from men's lodge door. Downtown Tipton. |

When you love old houses and

want them restored, salvage can feel creepy, like you’re stealing wallets and

jewelry from a dying person. I’ve had a house give me a cry of mercy (or I was

projecting it onto the house myself in sympathy), saying, “Why are you doing this to me?”

Once I stripped an entire turn-of-the-century farmhouse in Henry County. Six

months later I decided to drive by and grab a piece of hardware I knew I’d left

only to find the house crawling with workers renovating it.

That made for a pretty shitty

feeling.

The doors, floor grates,

woodwork, transom windows, lightening rods–you name it, were back in my

Hamilton County garage. I called the farmer who’d sold me the rights and asked

what happened. He said, “Somebody called and wanted to buy the house and a

couple acres, so I sold it. But don’t feel bad. They hate old houses. They want

to make it like a new house.

That made for an even

shittier feeling. Like I was Dr. Frankenstein and I’d taken all the good parts,

leaving someone with the dumb creature that was good enough for their

homogenized sensibilities.

Some houses don’t make you

feel anything. And dumpster diving is that way, too. At an old house

construction site, the dumpster is the organ donor repository. You’re

disconnected from the donor. But at several old houses I got a tingling on the spine and hair stood up on my arms, like ghosts were watching me, outraged as I dismantled their stairway with the

handrail they’d run their hands along for a lifetime–gripped as a toddler when

learning to walk and eventually gripped in feeble old age, not

understanding that I was saving it from going to a landfill or being burned as fire department training.

Some houses don’t make you

feel anything. And dumpster diving is that way, too. At an old house

construction site, the dumpster is the organ donor repository. You’re

disconnected from the donor. But at several old houses I got a tingling on the spine and hair stood up on my arms, like ghosts were watching me, outraged as I dismantled their stairway with the

handrail they’d run their hands along for a lifetime–gripped as a toddler when

learning to walk and eventually gripped in feeble old age, not

understanding that I was saving it from going to a landfill or being burned as fire department training.

Still, more times than not, the

houses felt welcoming, especially on warm, sunny days, like they understood

completely what you were doing and why you were doing it, and glad to be of

service to another old house.

My salvage experiences

inspired my second novel, The Salvage Man, a story about a man trying to

salvage his own life, while he strips a Civil War era farm house.

“Kurt Meyer’s The Salvage Man is a gentle Midwestern fantasy made up of one treasure after another. Part historical fiction, part love story, and part rumination on modern day life, this novel asks hard questions about the world we live in and the world we leave behind. I couldn’t put it down.”

Larry D. Sweazy, author of A Thousand Falling Crows

“Meyer turns the pages of history with gentle care and a warm heart, creating a story I’ll remember forever. Thank you Kurt Meyer for opening a door to my beloved town’s past and allowing me to travel the streets and meet the people of Noblesville 1893.”

Susan Crandall, Author of Whistling Past the Graveyard

Thoroughly enjoyed reading this.

ReplyDeleteThanks Victoria!

ReplyDeleteI am intrigued by the axe head found under the foundation... We had a similar experience when razing an addition on our 1880's Madison County farmhouse. An EXTREMELY old (allegedly) spear point found right under the garage foundation - so perfect and grey that my husband thought it was plastic water line. Do these things migrate upward from below? I can't imagine that the folks who poured that concrete originally wouldn't have noticed it...

ReplyDelete